Recognizing and addressing identity-based harm in schools

10/19/22

Written by Dr. Emily Meadows & Alysa Perreras

Alysa

’What exactly do you hope to gain by trying to determine here what constitutes trauma?’

This was the question my therapist posed when, yet again, after sharing an experience I had in school, I would immediately follow with some version of, ’I mean, it is normal kid stuff. It’s not like I was abused or traumatized’.

The irony is not lost on me now that I would consistently try to minimize experiences I’d had in my schooling as “not traumatizing” while speaking about them in my adult life with a licensed therapist.

My sister and I were grateful to have a family that could rally the funds and make the necessary sacrifices for us to attend a private school, one highly celebrated for its academic excellence. This education positioned me well for success later in life and provided me with opportunities I may not have had if I had attended a local public school.

My sister and I were also two of maybe five children of color at that school with working class parents who had both immigrated to the United States from other countries. It meant I was often—in the cafeteria, on the soccer team, in youth group and in the classroom—reminded of my otherness.

While some of those instances were more innocuous than others, what I have realized is that what I had normalized as “just kid stuff”, often because that is how the adults in my school treated it, was actually deeply detrimental to my sense of self and resulted in identity-based harm that I would be unpacking in my therapist's office years later. And I am not the only one .

An abundance of research explores racial battle fatigue , the psychological stress caused by ongoing daily experiences of racism. Additional research highlights how identity-based marginalization in schools can lead to ongoing harm and trauma . Yet, too many of our educational systems are not equipped with the knowledge and skills to address this type of harm.

Child safeguarding through an equity and belonging lens

Emily

*Sensitivity Warning: Suicide

As an LGBTQ+ consultant for international schools, I am distressed but not surprised that quite a number of clients call me initially because they are concerned about a student who is expressing suicidality, and the student is lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, or another identity beyond cisgender, heterosexual .

My lack of surprise is because a robust body of research has already demonstrated the significant increase in risk for suicidal ideation and attempts amongst LGBTQ+ youth compared with their cisgender, heterosexual peers.

This reality has led to the misconception that being LGBTQ+ is inherently riskier than being straight.

It’s a misconception because there is nothing at all risky about an LGBTQ+ identity unless the social context around us is stigmatizing, marginalizing, and discriminatory of LGBTQ+ people.

Social conditions that foster identity-based harm contribute to an increased risk of negative mental health outcomes, including suicide .

Indeed, these risks have been directly tied, in part, to the experiences of identity-based marginalization operating within schools .

However, the converse of this negative relationship is that, when education systems actively and effectively work to reduce stigma and marginalization, the impact is significant: suicidality goes down .

Let us not oblige another generation to work through their identity-based harm in therapy as adults; we can do better.

For schools intent on cultivating safety, we must understand how identity-based harm puts people with marginalized identities at risk of harm, and we must prevent and correct this inequity in our communities now.

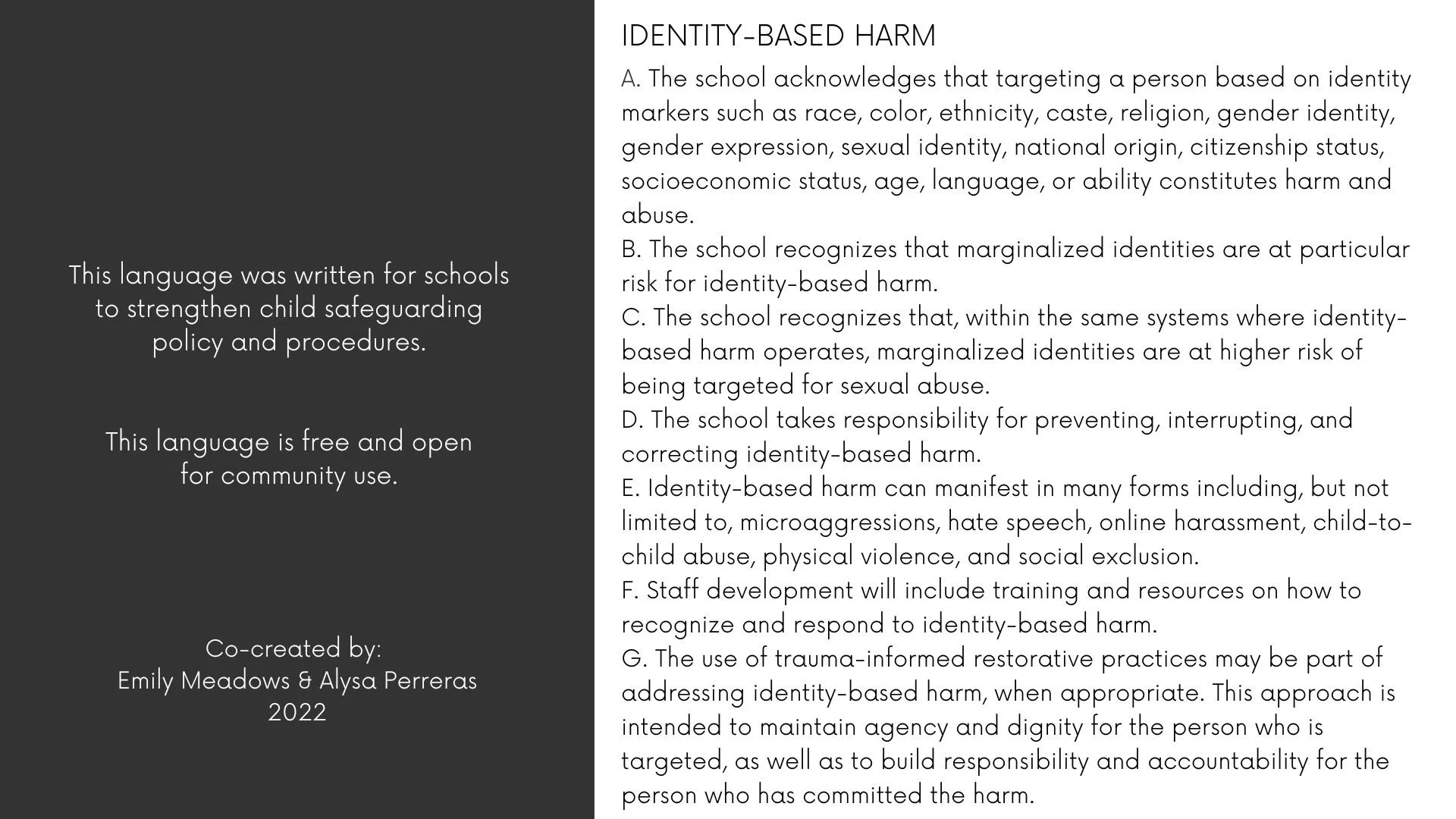

Recommended language for schools and educational systems

We designed the language below for use by and for educational systems to guide those seeking to build more robust protections against harm in schools and strengthen existing child safeguarding measures.

You’ll find seven key texts, along with supporting evidence and resources.

We encourage you to use this language within your own policies and procedural documents and to pair the commitment with concrete measures to ensure implementation with fidelity throughout your communities.

This is a useful resource for those interested in and responsible for child safeguarding. The language can be adopted immediately so the focus will be on moving forward with relevant actions.

About the authors:

Dr Emily Meadows PhD is an LGBTQ+ Consultant for International Schools

Alysa M Perreras is Inclusion, Belonging, and Antiracist Consultant and Researcher, Inclusion Manager, Netflix LATAM and Doctoral Student, Education for Social Justice, University of San Diego.

References:

Williams, M.T., Holmes, S., Manzar, Z., Haeny, A., & Faber, S. (2022). An Evidence-based approach for treating stress and trauma due to racism. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2022.07.001 (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2022.07.001)

Saleem, F.T., Howard, T.C., & Langley, A.K. (2021). Understanding and addressing racial stress and trauma in schools: A pathway toward resistance and healing. Psychology in the Schools, 1.

Call-Cummings, M. & Martinez, S. (2017). ‘It wasn’t racism; it was more misunderstanding.’ White teachers, Latino/a students, and racial battle fatigue. Race, Ethnicity & Education, 20(4), 561–574.

Killen, M. & Rutland, A. (2022). Promoting fair and just school environments: Developing inclusive youth. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 9(1), 81–89.

Carroll, A. & Mendos, L. R. (2017). State-sponsored homophobia: A world survey of sexual orientation laws: Criminalization, protection and recognition. International Lesbian and Gay Association.

Foucault, M. (1980). In C. Gordon (Ed.), Power/knowledge: selected interviews and other writings 1972-1977. The Harvester Press.

Lorde, A. (1983). The Master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house’. In Moraga, C. &

Anzaldua, G. (Eds.), This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color. New York:Kitchen Table Press.

Heron, B. “‘Global Citizenship’: A New Manifestation of Whiteness.” Critical Race and Whiteness Studies Journal, no. First Glimpse (2019): 1–14.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). (2016). Out in the open:Education sector responses to violence based on sexual orientation and gender identity/expression. Paris, France: UNESCO.

Kosciw, J.G. (2016). International perspectives on homophobic and transphobic bullying in schools. Journal of LGBT Youth, 13(1-2), 1-5.

Iván Gelpi, G. & Montes de Oca, D. (2020). Heteronormatividad Institucional en Enseñanza Media: La Percepción De Los Adolescentes De Montevideo. Athenea Digital (Revista de Pensamiento eInvestigación Social), 20(3), 1–26.

Allen, R.L. & Liou, D.D. (2019). Managing Whiteness: The Call for Educational Leadership to Breach the Contractual Expectations of White Supremacy. Urban Education, 54(5), 677–705.

Atteberry-Ash, B., Walls, N.E., Kattari, S.K, Peitzmeier, S.M., Kattari, L., & Langenderfer-Magruder, L. (2020). Forced sex among youth: Accrual of risk by gender identity, sexual orientation, mental healthand bullying. Journal of LGBT Youth, 17(2), 193-213.

Smith, D.M., Johns, N.E., & Raj, A. (2022). Do sexual minorities face greater risk for sexual harassment, ever and at school, in adolescence?: Findings from a 2019 cross-sectional study of U.S. adults. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(3-4), NP1963-NP1987.

Thompson, M.K. (2022). Sexual Exploitation and the Adultified Black Girl. St. John’s Law Review, 94(4), 971–988.

EXPLOElevate. (2022). Making the hidden visible: The lived experience of DEIJ Practitioners in independent schools. Retrieved from: https://elevate.explo.org/making-the-hidden-visible-the-lived-experience-of-deij-practitioners-in-independent-schools/ (https://elevate.explo.org/making-the- hidden-visible-the-lived-experience-of-deij-practitioners-in-independent-schools/).

Irby, D., Green, T., Ishimaru, A., Clark, S.P., & Han, A. (2021). K-12 Equity Directors: Configuring theRole for Impact. Chicago, IL: Center for Urban Education Leadership. Association of International Schools in Africa. (2014). Child Protection Handbook. Retrieved from:https://www.icmec.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/AISA-Child-Protection-Handbook-3rd-Edition.pdf (https://www.icmec.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/AISA-Child-Protection-Handbook-3rd-Edition.pdf)

Draugedalen, K., Kleive, H., & Grov, Ø. (2021). Preventing harmful sexual behaviour in primary schools: Barriers and solutions. Child Abuse & Neglect, 121.

Tarr, J., Whittle, M., Wilson, J., & Hall, L. (2013). Safeguarding children and child protection education for UK trainee teachers in higher education. Child Abuse Review.

Watson, K. (2018). Addressing violence, trauma, and discrimination in the education system: An examination of the training needs of title IX coordinators [ProQuest Information & Learning]. In Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences (Vol. 79, Issue 8a).

Morrison, G.F. & Ristenberg, N. (2019). Reflections on twenty years of restorative justice in schools. In Osher, D., Mayer, M.J, Jagers, R.J., Kendziora, K. & Wood, L. (Eds.), Keeping students safe and helping them thrive: A collaborative handbook on school safety, mental health, and wellness (pp. 295-327). Praeger: Connecticut, USA.

Gomez, J.A., Rucinski, C.L., & Higgins-D’Alessandro, A. (2020). Promising pathways from school restorative practices to educational equity. Journal of Moral Education, 50(4), 452-470.

The Human Rights Campaign Foundation. (2022). Glossary of terms. Retrieved from: https://www.hrc.org/resources/glossary-of-terms (https://www.hrc.org/resources/glossary-of-terms).

Carson, J. (2018). Greater suicide in LGBT youth. Nature Human Behaviour, 2(12), 886.

Gorse, M. (2020). Risk and protective factors to LGBTQ+ youth suicide: A review of the literature. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal, 39(1), 17-28.

Jadva, V., Guasp, A., Bradlow, J.H., Bower-Brown, S., & Foley, S. (2021). Predictors of self-harm and suicide in LGBT youth: The role of gender, socio-economic status, bullying and school experience. Journal of Public Health. Oxford, England.

Hatzenbuehler, M.L., Birkett, M., Van Wagenen, A., & Meyer, I.H. (2014). Protective School Climates and Reduced Risk for Suicide Ideation in Sexual Minority Youths. American Journal of Public Health, 104(2), 279-286.